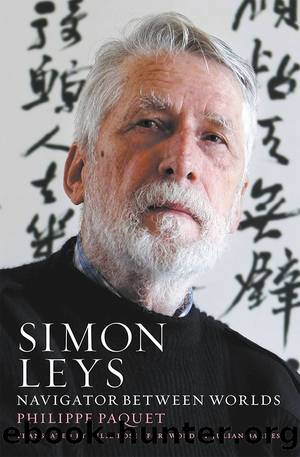

Simon Leys by Philippe Paquet

Author:Philippe Paquet

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd

We Are All Chinese

Simon Leys had placed Chinese Shadows under the patronage of Lu Xun, or Lu Hsun, quoting as an epigraph40 the passage in which Lu Xun, who was without a doubt the most irreverent of Chinese writers, claimed he felt like applauding the foreigner who, when invited to a banquet, would not hesitate to decry the current conditions in China, regardless, in the name of the Chinese people. That man, Lu Xun reckoned, deserved to be called ‘a truly honest man, a truly admirable man’. Leys undeniably aspired to be such a man in his work as a sinologist, and he shared the notion Lu Xun had of the role of the writer as ‘a permanent critic of power – of any power, including revolutionary power, towards which he nourished a healthy scepticism’.41

As well as writing two or three essays on Lu Xun, Leys sprinkled his work with reflections and judgements borrowed from a man whose sensibility vied with his irony. He dreamed for a long while of writing a book on him and to that end accumulated, over fifteen years, ‘a mass of miscellaneous material’. This information, which meant he even knew what brand of cigarettes Lu Xun preferred or how ‘frayed’ the underpants he wore were, was stored ‘in a bundle of index cards that I only had to get into shape,’ he said.42 Alas, the day before moving house one time, Leys put his index cards away so carefully he never found them again.

Meanwhile, in 1975, he had decided to translate Ye Cao into French, under the name Pierre Ryckmans. Lu Hsun had brought out this anthology of poems in 1927, a period that, on an artistic plane, corresponded to ‘the richest and most intense phase of creativity of Lu Xun’s career’. ‘The type of exploration which takes the author to the shifting frontiers of the real and the void, waking and dreaming, conscious and unconscious, gives it a “modernity” (in the Western sense of the word) that sets it apart not only from all his other works but also from the whole of twentieth-century Chinese literature,’ he remarked.43

Ryckmans prefaced the translation with an introduction titled explicitly: ‘Lu Hsun’s “Weeds” in the Gardens of Government’. In that introduction he developed a theme already outlined in Chinese Shadows: as early as his ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art’ of May 1942, Mao had dismissed Lu Xun on the grounds that the satire and pamphlet genres he’d used under the Kuomintang regime (born in 1881, the writer died in Shanghai in 1936) no longer had any point in the revolutionary China he would head. For the Maoists, who had made the author of A Madman’s Diary and The True Story of Ah Q a ‘precursor’ of the Cultural Revolution, the Great Helmsman and the great writer had, on the contrary, always had an unfailing admiration for each other. So, the publication of Ryckmans’s little book at ‘10/18’, in Viénet’s ‘Bibliothèque asiatique’, was a sacrilege.

‘Like

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11075)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6875)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5896)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4736)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4600)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4221)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(4003)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3984)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3817)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3724)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3681)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3601)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3527)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3443)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3372)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3320)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3237)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3237)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3223)